Systems Surprise, Systems Suspense, and Eating Shit at Mess Adventures

Here’s a question, what’s the funniest joke you’ve seen a game pull off? What about the most impressive - is that the same? I have fond memories playing Fallout: New Vegas as a preteen, right in that sweet spot where a single bit of media could rewire my entire sense of humour (Arrested Development and the Cornetto trilogy were other such offenders). Half of, say, Fantastic’s lines could just as easily have come from a Gob Bluth or a Gary King. “They asked me how well I understood theoretical physics. I said I had a theoretical degree in physics” is a great gag, but it’s one told with the same techniques of wordplay and characterisation afforded to film and TV. Are there other, subtler ways of telling jokes exclusive to an interactive medium?

Early on in the roguelike Hades, you’ll likely run into Supergiant’s take on Sisyphus: a cheery chap with an even cheerier boulder (look at that big fella’s winning smile!). You’ll just as likely pick up on the allusion to that old philosophical question, is Sisyphus happy? More than cheap reference humour, this is the game taking its genre conventions and using them to gently poke fun at you, the player. After all, how could Hades not characterise Sisyphus like this? If there was no meaning to be found in a repetitive and unending task - you wouldn’t be playing a roguelike, would you? The worst thing one can to a joke is over-explain it, but I do want to tie this in to the more general philosophy of humour. For the philosophy Arthur Schopenhauer, humour is “the suddenly perceived incongruity between a concept and the real”. Conceptually, that Sisyphus could be happy is absurd; in reality, you are; ergo: funny.

…Okay great. But how does any of that make this a joke?

Mess Adventures is an extremely mean platformer. It is also, with little dialogue or writing at all, extremely funny. I’d liken it to prank humour for how punishingly difficult it is, but there’s more at play here than just a steep difficulty curve. It’s not that its rules are hard to execute on, it’s that Mess Adventures is willing to change those rules on a whim. In Fallout and Hades we’ve seen jokes told through content (assets like writing, art, sound), but here is a game making full use of its systems (design, scripting, code) to be outlandishly unfair. Or as Tom Walker, the comedian and mess-adventurer captured above so eloquently puts it,

I knew it! I knew- do you see? Do you see they changed the fucking layout?! They-th-th-th-th-th-they took it away!

Surprise! It’s a Systems Design blog

Okay, big glaring caveat before I go any further: I am not a systems designer. I am not an authoritative voice on systems design. What I am is a programmer, and as a programmer I do believe it’s my responsibility to approach my work with some degree of critique - especially as it relates to the systems I’m personally implementing. So in this post, I thought I’d share two related concepts, systems surprise and systems suspense, and use them as a lens to reflect on my own formative experiences with games.

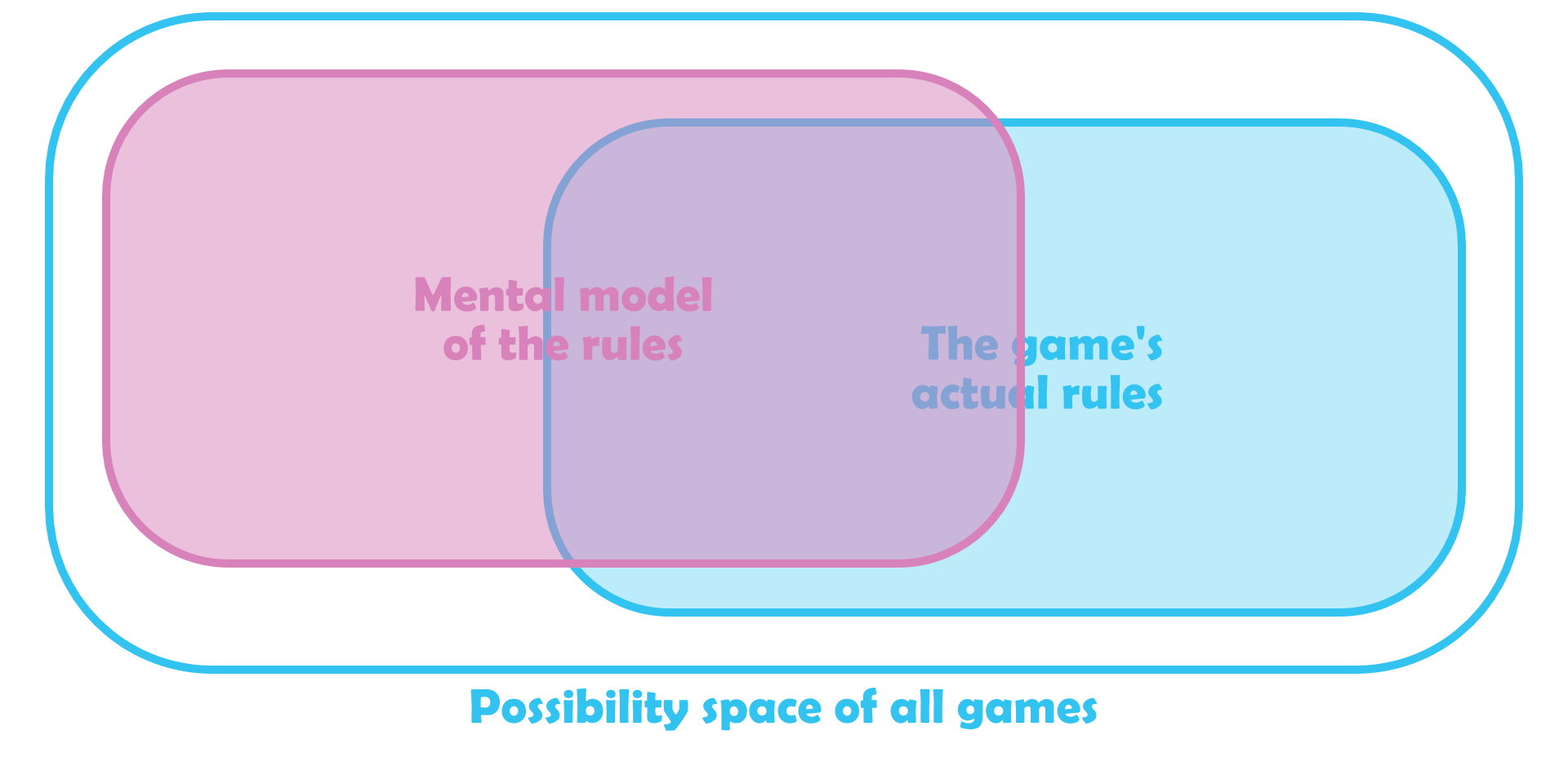

Let’s start by thinking about games in the abstract (this section is shamelessly cribbed from the seminal Understanding Systems Suspense, feel free to skip ahead if you’re already familiar). A videogame is a formal, computational system, governed by its rules and processes. The player can’t know these rules for certain - not without access to the codebase - so must reverse engineer them by making inputs and interpreting their outputs… playing the game, in other words. A mental model is the reversed engineered framework that maps their understanding of how the game operates.

Mental modelling is best understood as a continuous process. Influenced by publicity, franchise/genre history, etc., player expectations start to form long before booting up a game, and continue to develop long after completing its tutorial. Indeed, being able to interpret and critique the underlying logic of games is fundamental to the gameplay experience. Alexander Galloway has argued,

Video games don’t attempt to hide informatic control; they flaunt it. Look to the auteur work of game designers like Hideo Kojima, Yu Suzuki, or Sid Meier. In the work of Meier, the gamer is not simply playing this or that historical simulation. The gamer is instead learning, internalizing, and becoming intimate with a massive, multipart, global algorithm. To play the game means to play the code of the game. To win means to know the system. (Allegories of Control, in Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture, p. 89)

While other genres like rhythm games, precision platformers, and extraction shooters of course demand significant physical skill, I agree that mastering a game is analogous to mapping out an accurate mental model for it. It’s as hard to progress through any game without learning how it works as it is to learn how it works without enough progress; you can’t have one without the other.

Mental Models. Mental models exist in the possibility space. The model above has a solid, well-defined boundary (the player is confident they understand the systems of the underlying game), but its shape is misaligned (they are confidently wrong)

Mental Models. Mental models exist in the possibility space. The model above has a solid, well-defined boundary (the player is confident they understand the systems of the underlying game), but its shape is misaligned (they are confidently wrong)

The shape of mental model represents the set of rules and processes believed to describe a game. We can think of it as a boundary in possibility space, one separating what is possible from what isn’t. Systems surprise is thus defined as the sharp and sudden change in the shape of a player’s mental model into a new and noticeably different one. Where Bioshock epitomises so-called content surprise with its famous twist, Fez and Inscryption are games that are recontextualised over and over by big, genre-shattering systems surprises. Of course, you’ll already know how shocking a shift in rules and assumptions can be if you’ve ever been caught out by a mimic chest or the dreaded second healthbar.

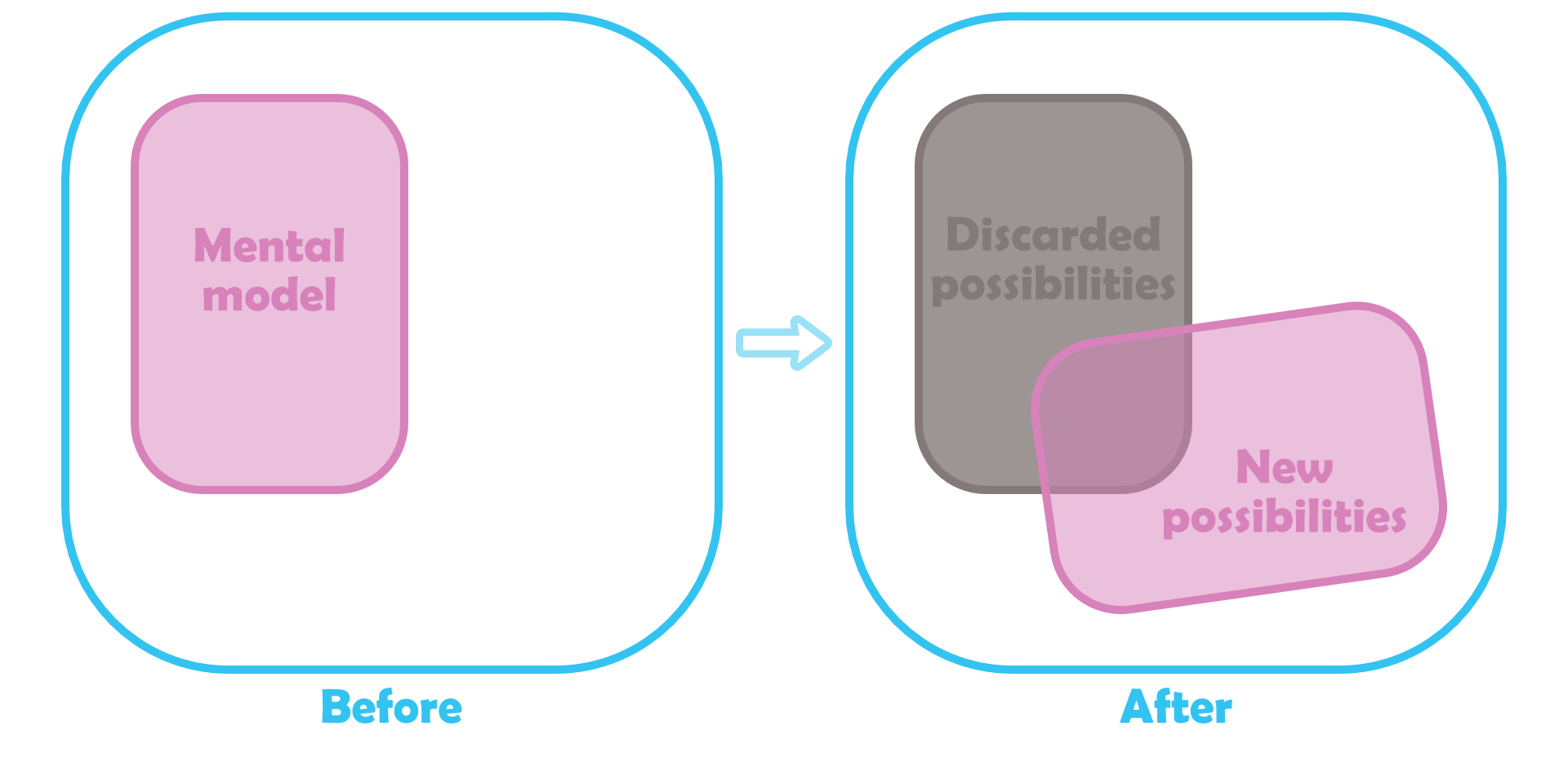

Systems Surprise Understanding Systems Suspense emphasises systems surprise must necessarily recontextualise a player’s prior experience. It has a shearing effect on their mental model, illustrated above. By contrast, content surprise is purely additive: it might open up new and unexpected gameplay possibilities for the player, but possiblities that nonetheless cohere with their existing understanding of the game.

Systems Surprise Understanding Systems Suspense emphasises systems surprise must necessarily recontextualise a player’s prior experience. It has a shearing effect on their mental model, illustrated above. By contrast, content surprise is purely additive: it might open up new and unexpected gameplay possibilities for the player, but possiblities that nonetheless cohere with their existing understanding of the game.

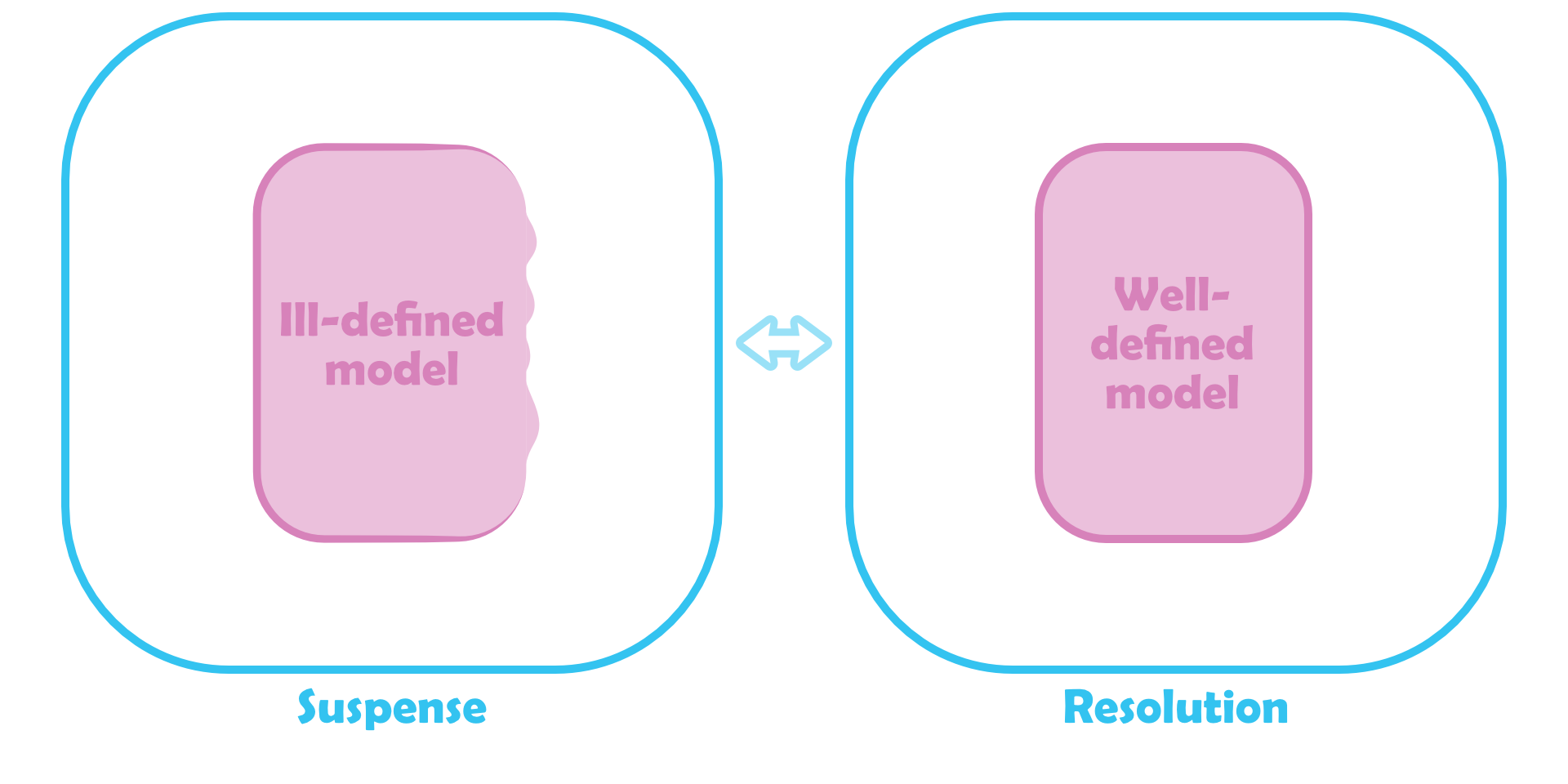

Suspense, on the other hand, is a matter of fidelity: the player’s confidence in the shape of their mental model. Where the boundary is solid, the player believes they understand a game’s rules; where it is fuzzy and ill-defined, they are able to arrive at several such (contradictory) possibilities. In these terms, systems suspense is the state in which the player is actively and excitedly aware of a ill-defined edge to their mental model of the game, the by-product of their known unknowns.

Systems Suspense A player’s sense of systems suspense runs parallel to their content suspense over how plot, character arcs, etc., might resolve. Suspense (in either form) demands not just uncertainty, but also an active engagement with it.

Systems Suspense A player’s sense of systems suspense runs parallel to their content suspense over how plot, character arcs, etc., might resolve. Suspense (in either form) demands not just uncertainty, but also an active engagement with it.

Understanding Systems Suspense gives many use cases for how and why designers might use this framework, but it is not exhaustive. Where it talks about using systems suspense and surprise to ellicit specific emotional responses, it focuses predominantly on fear and loss. If the player realises their understanding of a game is incorrect or incomplete, it can absolutely undermine their sense of security. That’s why mimic chests always get a fright out of me at least. However, it would be wrong to think upending a mental model can only be played for tension or outright horror. That’s why this blog post (and I’m rather excited because I really haven’t seen this anyone writing about this before) is focused on an altogether different affordance of systems design - getting a laugh.

Embedding Humour with Systems Surprise

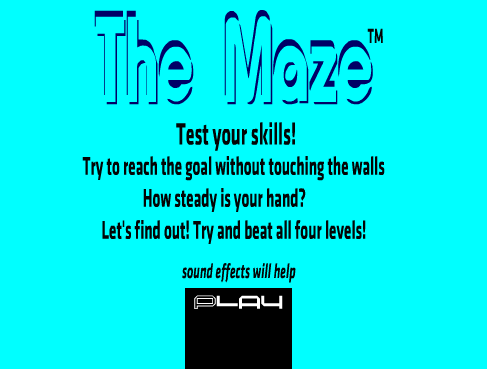

Systems surprise is, in Schopenhauer’s terms, the sudden perception of incongruity between a mental model and the actual rules of a game. Certainly, this tracks with our reading of Mess Adventures, with these surprises acting as the ludic equivalent of one-liners. The player’s mental model snaps from one well-defined shape (one where the ground cannot simply disappear out from under them) to another (one where it can), with no change in fidelity per se. And where Mess Adventures subverts the implicitly-understood genre conventions of 2D platformers, a more brazen game will just straight up lie to you. Browser games might be a little bit lowbrow, a little bit passé, but for all its simplicity Scary Maze Game remains as instructive an example of this design pattern as any.

If you recognise this UI you may be entitled to compensation. Scary Maze Game is ostensibly about precision, the player being challenged to guide their cursor through four levels of increasingly difficulty. But there are only three levels, and there is no way to win - a reality that comes suddenly, shockingly into focus when the game cuts to an infamous jumpscare at the crux of Level 3.

In both games, systems surprises are something that happen to (and at the expense of) the player. In both, the comedy lies in their being deliberately unfair, with no way of anticipating that unfairness in advance. The player does need to progress far enough to discover each joke, sure, but neither is predicated on player agency. Instead, they exemplify how systems surprise lends itself to ‘one-liners’ embedded - predetermined, more or less - by the designer.

But comedy doesn’t begin or end with one-liners. If you’ve ever heard Norm Macdonald’s moth joke, you’ll know how much craft goes in to setting up a gag, how much comic tension can be wrung out of the fact you just can’t tell where it’s going. Suspense is followed by surprise; the audience’s anticipation of the punchline heightens the eventual moment of release. This too can be affected on a systemic level, particularly when designing puzzles.

Now, Understanding Systems Surprise recognises “puzzle games as a genre commonly use [a] pattern of setting up rules and then bending them” in how their systems are designed. However, it doesn’t make explicit how much puzzles can resemble a classic setup and punchline structure. Suppose you present a player with two separate mechanics. You tutorialise them independently of one another. Then, you put them both in the same level for the first time: presumably, they’ll both be necessary to complete the level, creating a state of systems suspense as the player maps out how exactly these two separate systems interact. This is, in other words, game designer Arvi Teikari’s philosophy towards puzzles:

Quote from Arvi Teikari here.

Those eureka moments where systems suspense is resolved by a systems surprise are naturally rewarding, but they can also serve as moments of levity. Once you’ve created a logical paradox to complete a level of Patrick’s Parabox or accidentally disembodied yourself in Teikari’s own Baba Is You, you’ll know some solutions are so out of left field you can’t help but laugh. It’s not a coincidence that both installments of Mess Adventures pastiche Baba throughout. My own, personal favourite example of this design pattern, though, once again hails from the bygone days of Adobe Flash…

Impossible to Replicate To get from A to B in question 5 of The Impossible Quiz, the player has to completely disengage with the systems of the game and move their cursor around the outside of its window - a joke that incidentally did not translate to mobile ports on account of touchscreens. The medium is the message, eh?

Emergent Humour and Systems Suspense

When Understanding Systems Suspense describes how suspense can manifest without surprise, it is characterised as a “dawning realization… notable for how much it allows a player to look back on their past experiences in a new light”. That feeling of dawning realisation, it doesn’t strike me as an conducive to telling jokes - or at least, it didn’t until I circled back to Arrested Development. In its heyday, the sitcom was notorious for how far in advance it’d telegraph certain punchlines. What makes the sight gags I’ll only catch on a second or third or seventh rewatch so funny is not so much the jokes themselves, but the fact they’ve been staring me in the face the whole time.

Confession time: I have a guilty pleasure when it comes to replaying RPGs. I am not a sadist (nor an achievement hunter) but if I’m starting New Game+ it’s to respec my character as a truly horrible git. Even in Fallout: New Vegas, where going all-in on Caesar’s Legion can be played harrowingly straight, I still find this perverse humour to romping through the Mojave Wasteland and seeing just how much of a mess I can make. Amongst Merlin Seller’s writings on inaction in games, she retells a similar experience with Batman: The Telltale Series. As is the Telltale style, every dialogue choice has a timer attached to it; Seller lets every choice time-out, finding humour in Batman’s stoic (non)responses as the plot unfolds in stony silence. Where I was only making “obviously wrong” choices at Fallout’s narrative level, she engages with an entire mechanic the wrong way altogether.

We’ve seen how surprise, whether embedded in systems or content, lends itself to top-down, authored jokes, but here the comedy is emergent, arising bottom-up through our own player behaviours. I have unresolved questions about narrative (how evil will Fallout let me be?), Seller has an unresolved mental model (how little will Batman let me play?); both of us go out of our way to resolve that suspense. Whether or not it pays off in an actually surprising punchline, I would argue any such wilfully obtuse playstyle is, if only in a self-reflexive sense, inherently funny. Obstinance, though, is an unkind word. Liam Mitchell might better recognise this as a form of subversive play,

Now this isn’t really the point of my post, but I do think there’s an interesting paradox here. One of Mitchell’s central arguments in Ludopolitics is how games represent power fantasies not only in the overt You too can be a cigar-chomping babe magnet like Duke Nukem! sense, but how they implicitely present systems of control. Completionism is the clearest manifestation of this, where Mitchell argues “ “ The perverse humour of Seller’s playthrough is it simultaneously represents an attempt to subvert, it is still informed by that completionist mindset

…But not always. Speedrunning is maybe the canonical example of subversive play for how… Maybe One of Grand Theft Auto IV’s speedrun niches is Gervais%. Ironically, the systems we’re using are much funnier than any of Ricky’s hack bits. Speedrunning categories in a similar vein include Punch Cuno, Nipple%, and the very notion of attempting a world record time at a game like Unfair Flips.1

1 As Cat Manning, co-author of Understanding Systems Suspense, puts it, "some people have decided they want to speedrun [checks notes] probability."

Jokes Done QuickAt AGDQ 2014, tool-assisted speedrunners showed off an altogether different Super Mario World exploit. Due to a memory leak(?) in the original game, runners were able to inject new code during play, turning the platformer into maybe the world's worst IDE. See for yourself: it absolutely crushes.

Take it one step further than that, even - forget subversive play, let’s talk straight up glitches. Games are held together with sticky tape, JIRA tickets, and dreams. Liam Mitchell

Is committing unsafe code really a radical act of systems design? Sure, whatever, that’s what I’ll tell my boss at my next performance review.

ooooouugghhghhh i took too long to write this post and now my conclusion is ruined

So, this last part is going to need a little context. In my job, I run weekly dev talks for my department, and one of them was on, well, systems suspense and surprise. This was back in August, and I wanted to write it up here but kept putting it off and putting it off because I just kept finding more things to say.

Now, Understanding Systems Suspense came out of Polaris 2023, this annual game design conference that’s publishing reliably interesting work. A few weeks ago, the reports from their 2025 session dropped, including one called… Mechanical Comedy In Games 🤡😂. Goddammit.

Once I got over that initial feeling of, well, that’s

Like I said, I’m not a systems designer; comedy is subjective; the line between content and systems is not particularly rigid; caveats abound. I do want to highlight, though, that systems can well facilitate humour and play without either surprises or suspense. Bennett Foddy’s whole oeuvre, from the browser-based QWOP, GIRP and CLOP through to last year’s AAA satire Baby Steps, relies on incredibly tight, transparent systems design. Foddy’s brand of ludic humour is no less derived from incongruity, but he prefers to draw that incongruity from the practical difficulties of operating conceptually simple controls.

As far as my own comedic sensibilities go, they more or less come down to two key points. Firstly, a game’s systems don’t begin or end where a designer intends them to. Humour can be embedded, but just as easily emerge as the player traces out the fuzzier edges of their mental model. Speed tricks and exploits, not to mention ROM hacks (see Kaizo Mario World, the original mess adventure) and mods (Thomas the Tank Engine in Alien: Isolation), can all become vehicles for subversive comedy with a little lateral thinking. To borrow a phrase from Galloway, they are ways players play on the code of a game.

And secondably, it’s never not funny to be an absolute dick to your audience.