LTO != PGO

Ballooning link times for fun and profit.

PGO is just LTO with extra profiling data, right?

Wrong! Just before the holidays, I found myself chatting to a senior dev at my work - - it’s been rattling around at the back of my head for the festive period.

Link-time optimisation (LTO) is what it says on the tin.

between my previous post about profile-guided optimisation (PGO), and another, much larger project of mine that I’m not quite ready to share just yet. But plenty of digital ink (pixels?) have been spilled on link-time optimisations (J. Ryan Stinnett’s guide being my personal favourite). I honestly don’t think

But, in the lead up to shipping Tomb Raider, a senior dev at Feral asked me a really quite good question,

Back to my colleague.

I think my mistake was imagining the optimisation steps in LTO is distinct from normal compiler optimisation

I figured oh okay, there’s a blog post in here.

which was enough to convince me a circuitous and more-than-a-little-self-indulgent answer might be in order.

LLVM, Revisited

I was, I’ll admit, a bit tricksy with how I wrote PGO, But Better. It’s not got any outright lies or outstanding corrections - I like to think I’m pretty rigorous in how I put these posts together - but like any programming blog I had to elide some finer points for the sake of clarity. You might remember I introduced Clang as my compiler of choice, the one I’ll be writing these blogs about. You might also remember that it’s the C/C++ frontend of the LLVM compiler infrastructure. What you won’t remember is where the linker fits into this infrastructure - I didn’t even mention it.

LLVM

But what even is a linker? [Definition of linker]. [Definition of modules].

Compile-time and link-time are, well, finicky concepts. Linking actually happens within llc, the LLVM static compiler!

How exactly does our source code pass through…

The LLVM Middle-End

Let’s look at this in a

LLVM IR

- To get even more granular (and this subsection is totally optional), LLVM translates to

a human-readable textual form, and a binary form often referred to as LLVM bitcode.

As an example of what this IR looks like, let’s take a minimal example. Here’s two modules I made earlier:

Using LLVM X.Y.Z, I can feed these in to…

Optimising…

Finally, linking with…

A Worked Example

Compile and decompile this example, play about!!

If there’s one idea I want to get across with this blog, it’s this: the linker makes more or less the same optimisations across multiple sources that compiler does within each source. If you understand one, you do understand the other.

Further example, undefined behaviour…

Link-Time Optimisations (LTO)

Describe w/o…

Full LTO

Thin LTO

Notes on linker caching here, actually get technical with it?

End that - this is the limit!

Fast(er) Link-Times

Describe the benefit of LTO as being faster, philosophy of link-times (especially as it relates to indie development). then…

If you’re working on an extremely large project, chances are you’re running distributed builds across a whole network of machines, with each taking responsibility for its own units of work. Full LTO, being single-threaded, also needs run on one single linker, but Thin LTO slots into a distributed system nicely. Here, machines receive their own [index files?], and can be […]. But I digress.

Unified LTO

Fat LTO

LTO && PGO

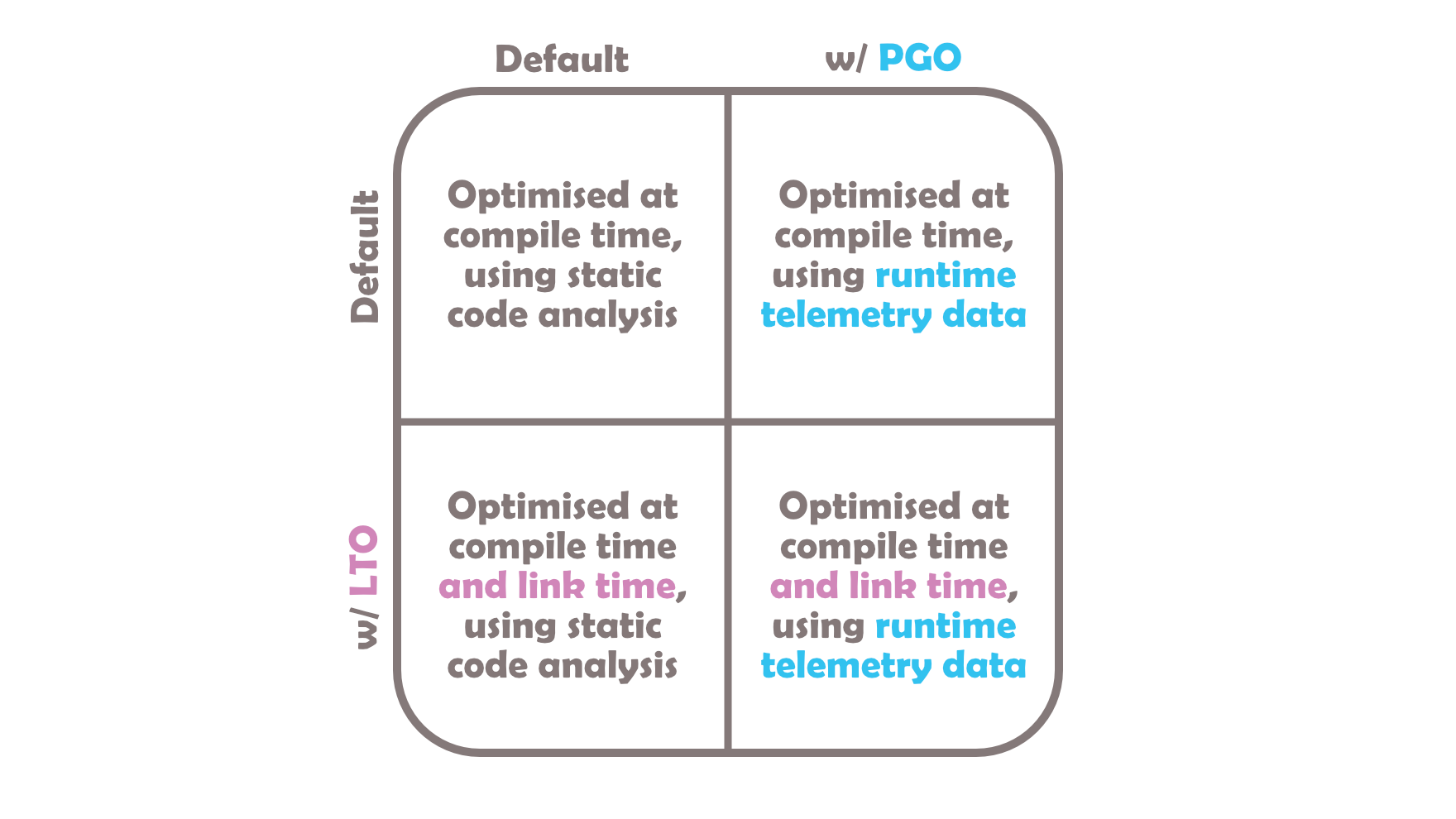

If LTO is “optimisation with knowledge of all sources,” PGO might be thought of as “optimisation with knowledge of how a source is used”. These are orthogonal properties, you can absolutely have either one without the other.

In theory, that is. In practice, MSVC won’t let you enable PGO without LTO because of how the compiler has been written; Clang and GCC, however, support either/or.